Decision soon on platinum process that can save power

Kelltech’s Keith Liddell interviewed by Mining Weekly’s Martin Creamer. Video: Darlene Creamer.

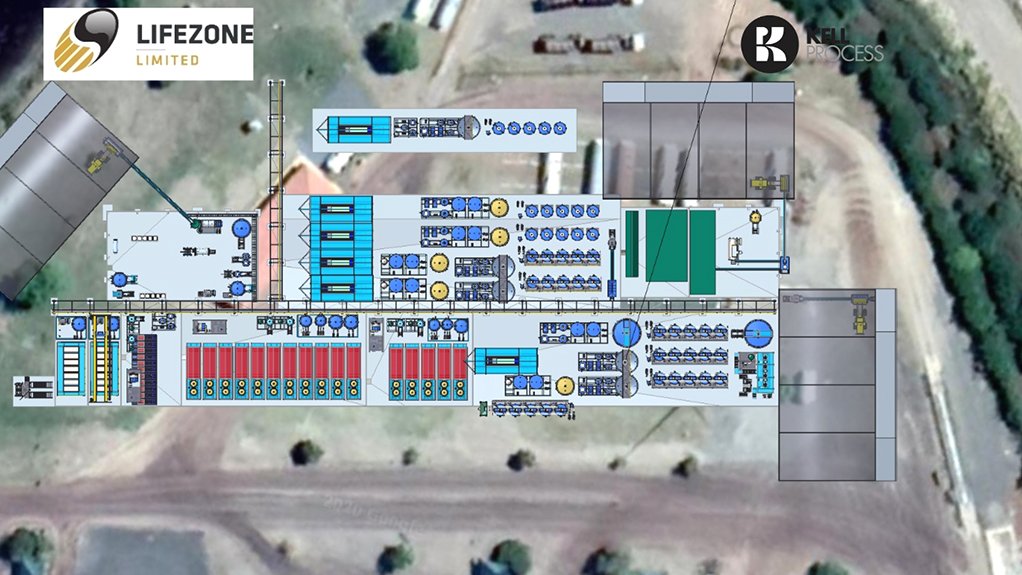

Layout of the Kell plant proposed for Sedibelo's Pilanesberg platinum mine.

Illustration of an autoclave that will be used by the Kell process.

JOHANNESBURG (miningweekly.com) – The definitive feasibility study for the installation of a revolutionary new electricity-slashing processing plant at Pilanesberg Platinum Mine in the North West will be completed next month, in time for an investment decision from the shareholders in KellTechnology South Africa, which are Pallinghurst’s Sedibelo Platinum Mines, the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) and Lifezone Limited.

The electricity consumption of the amazing Kell process is 20% that of the electricity consumption of smelting, the current conventional method of processing platinum group metals (PGMs). (Also watch attached Creamer Media video.)

Southern Africa’s current PGMs processing infrastructure is massively energy intensive, primarily through the use of the high-temperature smelting that originated more than 100 years ago.

The significant lowering of this colossal energy intensity would be of great assistance to South Africa’s struggling economy, as this country’s electricity shortage is one of the most prominent obstacles to a faster economic recovery, the South African Reserve Bank has categorically stated.

South Africa’s current PGMs smelting/refining sector over a year uses 5 000 GWh. In a hypothetical scenario where Kell replaced the current pyrometallurgical processes, nearly 4 000 GWh a year could be returned to the South African power pool.

The far-reaching Kell process comes at a third of the capital cost of smelting/refining and at half of its operating cost.

End products can be customised and the proposed Sedibelo Kell plant will be producing refined 99.95% PGM metal products.

Locked up ‘work in progress’ PGMs inventory is 90% lower, releasing working capital and shortening payment pipelines from several months for smelters down to a month or so. In fact, for a mining company that is currently selling concentrate, the release of locked up working capital can pay more than half of the cost of a Kell plant.

Kell’s ability to recover cobalt has resulted in discussions with potential South African companies that are interested in manufacturing electric vehicle (EV) batteries domestically in South Africa.

Kell’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from concentrate to final refined metals are only 19% of the CO2 emissions caused by the current smelting/refining route.

Kell emits zero sulphur dioxide (SO2) and converts the sulphide minerals into a stable and benign gypsum product and its water consumption is negligible.

Insensitive to the chrome content in the concentrate, Kell ensures that there are no harsh penalties when chrome levels are exceeded.

Kell produces refined metals at the mine site and thus generates more skilled jobs at the mine site.

Overall metal recoveries are comparable with traditional smelting-refining and in some cases higher.

The proposed Pilanesberg Platinum Mine plant has already obtained its environmental approvals.

HYDROMETALLURGY ECLIPSES PYROMETALLURGY

Kell is essentially a hydrometallurgical process, involving key elements being leached and re-leached.

There is a little pyrometallurgical bit in the middle involving material being put through a kiln to render the precious metals leachable again after having taken up base metals, but this involves only heating and not smelting.

Metaphorically speaking, the pyrometallurgy, through smelting, is the big sledgehammer being used to crack the nut and it smashes it to smithereens as a way of extracting benefit out of it.

“What we do is, with a pair of nutcrackers, just open it up and then extract the kernels out,” Lifezone director Keith Liddell explained to Mining Weekly during a Zoom interview in which he let it be known protection of the technology has been enhanced by four new patents granted globally, one for refractory gold concentrates that enables production of refined gold at the mine site without use of cyanide. Lithium, too, is in the development company's sights.

But the immediate strong focus is on the PGMs sector: “We’ve been extremely busy in essentially engaging the overall PGMs industry in Southern Africa but also to some extent globally. We’ve been developing feasibility studies, scoping studies and test work, batch test work, pilot test work and continuous test work.

“The industry is now well informed about Kell and in specific terms its operating costs and capital costs in relation to their own operations and they’re all waiting for the outcome from our first commercial installation.

“It’s the classic that we always see with new technology into the conservative mining industry – ‘don't be first but make damn sure you're second’.

“We appreciated that many years ago when we tied up with Sedibelo Platinum and Pallinghurst, and quickly after that the IDC, because we knew we had to have a Kell plant working on a mine somewhere before the balance of the industry would accept it.

“Sedibelo particularly is a company that wants to take its Pilanesberg Platinum Mine and vertically integrate it to produce some PGM metals and base metals at the mine site.

“In the last couple of years, and particularly this year, we further optimised the engineering into a fully modular plant format that includes PGMs refining and base metal refining,” Liddell told Mining Weekly.

The funding package is being finalised in conjunction with Sedibelo and the IDC, as shareholders of the Southern African Kell licence.

Several independent studies completed confirm the substantial decrease in CO2 and SO2 emissions from Kell compared with smelting and refining. "So, if the industry wishes to reduce the carbon footprint of its products, or rather, if the buyers of PGMs want lower CO2 inputs, then Kell is the obvious solution, Liddell said.

While there are zero SO2 emissions from Kell, many PGM smelters, and even new ones, burn the sulphide minerals to form sulphur dioxide that is released directly into the atmosphere.

With the help of acid plants and wet scrubbers, PGM companies are abating sulphur emission, but this does not remove 100% of the SO2, even though it comes at considerable capital and operating cost, Liddell noted.

UPPER GROUP TWO REEF

Kell’s insensitivity to the chrome content in the concentrate does not limit the rate that upper group two (UG2) reef, currently favoured by mining companies seeking optimum palladium and rhodium output, can be processed.

“We don’t care what the chrome content is in Kell feed as the chromite passes through the process undigested,” Liddell pointed out.

Moreover, base metal refining and PGMs refining are integrated directly into the Kell process, again at the mine site.

The Kell plant design for Pilanesberg will produce final refined platinum, palladium, rhodium 99.95% metals and gold 99.99% sponge, in addition to London Metal Exchange-grade nickel/cobalt/copper cathodes.

The materially lower cost of Kell has been demonstrated over a number of studies now, for different users and all types of concentrate, embracing UG2, Merensky, Platreef and Great Dyke reef.

TIMELINE OF EXPECTED CONSTRUCTION

The intention is to build the first Kell plant to process 110 000 t/y of high chrome and high rhodium concentrates from Pilanesberg Platinum Mine and a third-party.

“We have solidified the financial investors and are in the financial closing process. We have received continued strong support from our main shareholders at the IDC and Sedibelo. In parallel, the permitting process has been ongoing and several approvals are now in place,” Liddell disclosed.

The Kell plant design holds the potential to liberate the midtier miners to become ‘mine to market’ participants rather than depending on the majors to process their production.

Since each plant is custom designed for throughput, ore type and product type, each client can select the specific type of products that they want to manufacture. It can also play a role within existing smelter/refinery circuits, as a means of processing the concentrates that are more difficult to smelt or where a bottleneck exists, such as in base metal refining.

If a client has a precious metal refinery with spare capacity, as is the case for most of the industry, then the output from a Kell plant can feed into their existing platinum metal refineries.

RECOVERY OF COBALT CURRENTLY DESTROYED

The existing smelters and refineries in South Africa burn off most of the contained cobalt. In contrast, Kell recovers over 95% of the contained cobalt to refined metal product.

“There have been discussions with potential domestic South Africa companies that are interested to manufacture electric vehicle (EV) batteries domestically in South Africa. That is very interesting to us as the hydrometallurgical process provides a competitive advantage to customise the final end products into battery precursors such as nickel, cobalt and manganese.

“For instance, EV battery manufacturers in South Africa will be constrained in sourcing cobalt from outside South Africa, and recovery of cobalt from South African PGMs is of interest to them.

“Our initial Kell plant at Pilanesberg will have a cobalt recovery section, but more as a test facility to start with since the feeds to that plant, being UG2 are quite low. But we do see opportunity for a battery precursor, or even battery manufacturing plant to be sited next to a Kell plant,” Liddell said.

HYDROGEN ECONOMY

The PGMs industry has taken a knock since 2017 as a result of dieselgate, and effectively suspended capital projects for two years, but this year is seeing a reawakening with the rise in PGM prices and the lengthening demand horizon into the hydrogen economy. "Nothing has really changed in concept, but we have been fine-tuning our engineering designs, and of course defining the environmental metrics," Liddell added.

Mining Weekly reported several years ago that:

- to add Kell to a 250 000 oz/y PGMs operation would cost $65-million;

- Liddell patented Kell – the letters that make up his initials – as a smelting alternative in 1999 and has continued to fine-tune it ever since;

- Liddell first conceptualised Kell when, as a platinum junior in the 1990s, he was producing insufficient concentrate to justify investing in a smelter;

- Kell consumes a small fraction of the electricity that smelting consumes, 140 kWh of electricity for every ton of concentrate processed compared with 1 000 kWh of electricity for every ton of concentrate smelted;

- Kell requires no milling and makes use of standard pieces of off-the-shelf or out-of-the-catalogue equipment and because of its modularity, there is no need to sink large sums of capital into one big smelter ahead of time;

- the third stage of Kell is the first stage of the PGMs-refining process, in which the PGMs are brought into solution;

- the chemical brains behind the whole thing are those of Dr Mike Adams, who has a double PhD in chemistry and who worked with Liddell in the 1980s at South Africa’s State-owned minerals research organisation, Mintek;

- after graduating from Birmingham University in 1981 with a degree in minerals engineering, Liddell joined Mintek and two weeks later found himself optimising flotation recovery at Western Platinum’s first UG2 concentrator in North West;

- Liddell carried on working primarily in the platinum sphere during his time at Mintek, eventually helping to design and build the Kroondal platinum mine in 1997;

- it was then that he began conceptualising and then accelerating the development of Kell, which is ideal for juniors, who are paid only 80% of the value of concentrate by toll smelters; and

- juniors who choose to make their own metal on site benefit from lower royalties and beneficiation credits and reduce the cash lockup of selling their concentrate to majors and waiting four months to be paid.

Liddell is also a director Lifezone's licensee companies KellTech and KellTechnology South Africa.

Comments

Press Office

Announcements

What's On

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine

(print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Receive daily email newsletters

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1

PLUS

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors

including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

➕

Recieve daily email newsletters

➕

Access to full search results

➕

Access archive of magazine back copies

➕

Access to Projects in Progress

➕

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

SUBSCRIBEAll benefits from Option 1

➕

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports on various industrial and mining sectors, in PDF format, including on:

Electricity

➕

Water

➕

Energy Transition

➕

Hydrogen

➕

Roads, Rail and Ports

➕

Coal

➕

Gold

➕

Platinum

➕

Battery Metals

➕

etc.

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

➕

Multiple User names and Passwords for simultaneous log-ins

➕

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation